Skylab: The rise - and meteoric fall - of America's first space station

Full episode: Skylab crashes back to Earth

Back in 1979, it became clear that America’s first space station would be falling out of orbit. But when and where would it happen? In this LiveNOW & Then, we look back at how the media covered the sky-is-falling scenario.

HOUSTON - Decades before the International Space Station began orbiting Earth in 1998, NASA revolutionized extended human space missions with the 1973 launch of Skylab, America’s first space station.

It wasn’t the world’s first space station – the Soviets claimed that milestone in 1971 – but Skylab was much larger and more complex. It was abandoned a year after its launch and would take a few years for Skylab to fall back down to Earth.

For months, TV and radio stations across the world warned Skylab could land anywhere – and at any time. Scientists were able to predict that the crash was coming, but they couldn’t pinpoint when or where.

Here's a LiveNow & Then look back at the media frenzy behind the rise and fall of Skylab in 1979.

FILE - A photograph of the Skylab Space Station taken by astronauts on their way home in 1973 (Getty Images)

What was Skylab?

The backstory:

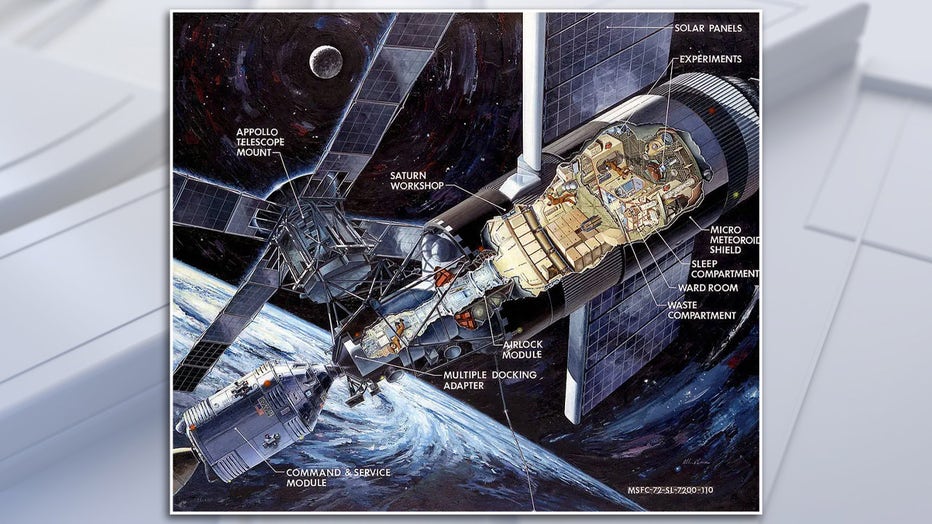

Skylab was the first American space station designed for longer trips to space. NASA wanted to prove astronauts could live and work in space for extended periods while learning more about solar astronomy, so they reworked the upper stage of a giant Saturn V moon rocket to be used as an Earth-orbiting space station instead.

By the numbers:

Skylab weighed a whopping 170,000 pounds, by far the heaviest spacecraft at that time. Skylab had three crewed missions, with three astronauts each, in 1973 and 1974, space historian David Hitt explained. It was occupied by astronauts for a total of 171 days.

A pre-launch NASA diagram showing the Skylab layout.

What they're saying:

"This is coming six months after the last footsteps on the moon," Hitt said. "America is transitioning out of lunar exploration into developing a sustained presence in Earth’s orbit. This is going to be the foundation for all of the amazing science that has been done over the last 50 years in space."

Despite early mechanical difficulties, the project was largely considered a success. Astronauts conducted nearly 300 experiments on board, including medical experiments on humans’ adaptability to zero gravity, solar observations and detailed Earth resources experiments.

A close-up view of Skylab on July 28, 1973 as the Skylab 3 crew approached for docking. (NASA photo)

After the final crew left Skylab in 1974, it remained in space for about five years. Hitt said NASA had hoped the space shuttle would be ready to visit Skylab at least one more time, but the shuttle took longer than expected to prepare. Solar activity was also higher than predicted during that time, which caused Skylab’s orbit to decay faster than NASA had hoped.

The summer of Skylab

As scientists began warning the public about Skylab’s potential reentry on Earth, media coverage ranged from informative to downright comical at times.

People made wagers on when and where it would land, while merchandise warned folks to write a will, "just in case." The San Francisco Examiner launched a contest to coincide with the spectacle: The first person to bring a piece of Skylab to the newspaper’s office would win $10,000.

Asked if the coverage was over-hyped, Hitt said, "100%, yes."

"My favorite story along those lines is a reporter from up in Houston drove down to Johnson Space Center to interview some of the astronauts about Skylab's reentry, and was kind of ready to nail them to the wall about how could you do this?" Hitt recalled. "And the astronaut said, well, statistically speaking, you endangered more lives by driving from your TV station to the NASA base than Skylab presents to the world."

Still, Hitt said, it’s human nature to worry about a 170,000-pound block of space debris crashing into Earth.

"Chicken Little, the sky is falling," Hitt said. "It's hard not to think about that."

Where did Skylab fall?

Timeline:

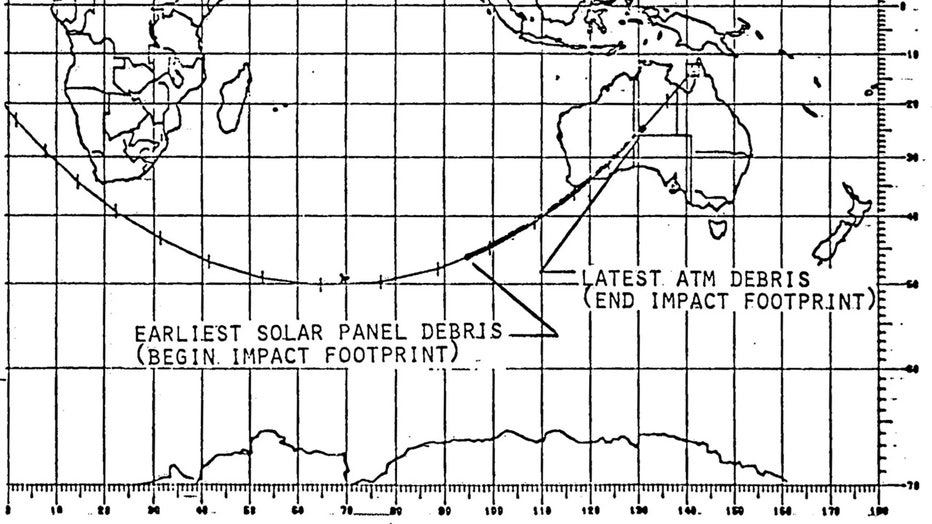

If you had bet on Australia, you would have been right. Skylab debris fell on the western part of the country and in the Indian Ocean on July 11th, 1979. Fortunately, no one was hurt and no significant property damage was reported.

An Australian teenager grabbed a piece of the space station and raced as fast as he could to California to cash in on The San Francisco Examiner’s contest. He returned home with $10,000.

Ground track of Skylab’s final orbit and the debris footprint in the Indian Ocean and Australia. (NASA image)

What are the odds?

Dig deeper:

While history often remembers Skylab as some kind of uncontrolled crash into Earth, Hitt is quick to point out that wasn’t the case.

"The truth is there was software that was written ahead of time to bring Skylab home. People were sitting on console at Mission Control in Houston, actively talking to the spacecraft, which continued to communicate and continued to respond to commands, even as it was breaking up, coming into the atmosphere," Hitt said. "It was kind of amazing how robust this spacecraft was."

Managers and flight controllers monitor Skylab’s 1979 reentry from Houston. (NASA photo)

Plenty of rockets have reentered from space since Skylab’s descent decades ago, but the chances of one landing on you or in your yard are still pretty slim.

"The earth is a very big place, and a whole lot of Earth is covered with water," Hitt said. "Of the part that's land, the place that our species has established a foothold is relatively uncommon. So the odds are when something comes in, purely statistically speaking, it's probably not coming down on you."

What about the International Space Station?

What's next:

The law of gravity reminds us that "what goes up, must come down," and the same is true for the International Space Station. Eventually, the ISS will return to Earth. But unlike Skylab, NASA is now much more capable of controlling when and where it lands.

"Planning is already underway today for the reentry of the International Space Station," Hitt said. "And so they’ll have a lot of advantages for reentry that Skylab didn’t have."

The Source: This report includes information from NASA and space historian David Hitt, along with archived coverage from KTVU, KDFW, KTTV, WITI, WAGA. FOX’s Megan Ziegler and Stephanie Weaver contributed.